Fancy 2016 update:

We all know that compost is an excellent fertilizer for plants. It is also a sensible way to deal with organic wastes. In my climate, one can construct compost bins and dump his or her organic material in and, after two years time, finished compost is ready to go. Seriously, two years? I don’t need compost in two years, I need compost this year – this month! And if I keep throwing crud onto my compost pile for two years, it will be huge! Furthermore, I have to start new piles to let the old piles mature so that I am not digging through garbage to get down to my compost at the bottom. There has to be a better way. There is. When in doubt, let nature help out.

Microscopic workers

Lovely things bacteria. Different species of them have adapted to survive in almost any environment on earth. Some can even exist in temperatures that would burn your skin in seconds. In fact, some can generate that heat themselves. Enter into our story thermophilic bacteria. These little darlings seem to be ubiquitous, waiting for the right environment to present itself so that they can have their own little barbeque. If enough of their food is served to them in the right proportions with the right amount of water and just a touch of heat to start them off, they will hold their own little party and really get things cooking, literally.

So you’ve guessed by now that we are going to partner with these little bacteria to create our compost. Well they need to eat, so here’s the composting rule: If it has lived, it can live again. Forget what other composting guides have told you about no weeds and no meat, both those are fine. We are just concerned with carbon to nitrogen ratios. Thermophilic bacteria like a diet that has 25 to 30 parts of carbon for one part nitrogen (i.e. ratios of 25:1 to 30:1 carbon to nitrogen). Now, I don’t want you to get the impression that you need to go out and buy scales and weigh your garbage. It’s not like bacteria are as fussy eaters as cats. As long as you know basically what is carbon-rich and what is nitrogen-rich, you can make composting more of an art than a science.

Common compost ingredients

| Material | Carbon:Nitrogen Ratio |

|---|---|

| Bark (Hardwood) | 223:1 |

| Bark (Softwood) | 496:1 |

| Coffee grounds | 20:1 |

| Fish | 3.6:1 |

| Grass clippings | 15:1 |

| Leaves | 54:1 |

| Manure (Cattle) | 19:1 |

| Manure (Chickens) | 10:1 |

| Manure (Horse) | 25:1 |

| Manure (Pig) | 14:1 |

| Manure (Sheep) | 16:1 |

| Paper | 800:1 |

| Poultry scraps | 5:1 |

| Sawdust | 500:1 |

| Straw | 80:1 |

Measuring compost ingredients

Again, you don’t need a scale. What you should take out of this is dry, brown things are high in carbon. Wet things that get stinky easily are high in nitrogen. Things that come out of your kitchen are going to be high in nitrogen. Dry plant scraps are going to be high in carbon. For most people, the hard part is going to be supplying the carbon, not the nitrogen. You might even need to hunt for someone else’s carbon-rich waste to get it. Your pile will basically be 2/3 carbon-rich material and 1/3 nitrogen rich material.

If you want to optimize speed, here’s a secret ingredient you can use: ash. Adding some fireplace ash will ensure that the pH doesn’t go too low. This will create a better environment for your bacteria, which will do the breaking down of the material.

A word of caution, though: If you use sawdust, make sure it is not from pressure treated lumber. Pressure treated lumber is impregnated with chromated copper arsenate, and unless your goal is cancer and cadmium poisoning leading to osteomalacia, you must avoid it at all costs. It is dangerous stuff.

Small pieces for faster composting

When I was a boy, I was not too good at cutting meat, particularly steak. I would pin the steak down and pry on it with my fork. The result all too often was that the steak would fly across the table and hit my older brother who frowned on that sort of thing. To avoid this, I would pick up the edge of the steak with my fork, bend down to my plate and chew on it. My mother frowned on this. She put a stop to this by cutting my steaks into small pieces for me. Problem solved.

Well, you need to do the same thing for your thermophilic bacteria. No, chucks of compost will not fly out of the compost pile and hit someone’s older brother if you don’t, but your pile will compost much better if you do. By chopping things up finely – ideally to pieces 1 cm long or less – you will be creating more surface area. More surface area means more area for more bacteria to munch away on the material in the compost pile. A small garden shredder can help you here. I have seen hand-powered choppers (a crank with a circular blade attached) in developing countries, but sadly I have not found such useful, human-powered choppers in Canada. If you like, you can throw in some larger, nitrogen-rich items once the pile has warmed up. The largest I’ve heard of was a roadkill rock wallaby. I was told that it melted away into nothingness inside the pile in about 6 days with only a shoulder blade remaining.

Mixing

Mix up your material – a pitchfork can really help you here. Add water it as you go until you can just squeeze a single drop from a handful of material. This is just the right amount of water for the bacteria to do their thing. Also, to get the thermophilic reaction going, there needs to be enough material for a sort of “critical mass” to occur. This will occur when piles are 1 cubic metre or larger. What this means in practice is a pile that is about shoulder height.

Day 4

With the mixing done and the watering right, set a tarp over the pile and leave it 4 days. (The tarp is so that neither rain nor evaporation messes up your water content.) On the 4th day, turn the pile with a pitchfork. Don’t skip the turning part because we are dealing with aerobic bacteria. They need air. Just put the top and sides in a pile next to the current pile and put what’s left of the old pile on top, checking to make sure the water content is right (by squeezing the material) as you go. Now the pile will essentially be inside-out. Once you rake the last bits of the old pile onto the new pile, it’s ready to cover up with the tarp. Have a beer if you like.

Day 6

On the sixth day, take the tarp off and stick your arm in the pile. If everything is going correctly, you will instantly pull your arm out, cursing my name. If the pile is composting properly, it should be around 70ºC inside – literally hot enough to cook with. This is why it is ok to put weeds in. Any weed seeds will be cooked to the point that they are not viable (if they aren’t just melted away in the compost). Turn the pile again checking the water content as you go. Sorry about burning your arm. Have a beer, you deserve it.

From Day 6

After day 6, turn the pile every 2 days, checking the water content as you go and putting the tarp back over the top each time. After about 18 days, you will have finished compost. If things are a little cooler where you are, it may take longer. If they are hot, you might match the best time I’ve heard, which is 11 days.

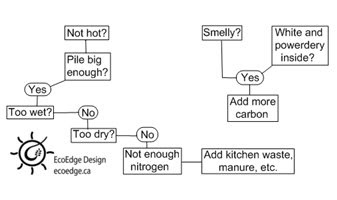

Troubleshooting

Things don’t always go according to plan. Here’s what to do if they don’t:

On day 6, you grit your teeth, stick your arm in the pile and find it is not hot. Is the pile big enough? One cubic metre is really big. If it’s not really big, make it bigger. If it is big enough, is it too wet? If it is, spread the material out and let it dry a bit. Is it big enough and not too wet and not too dry? Then there is not enough nitrogen.

Inside the pile is there a white powdery substance? If so, there is too much nitrogen, Add carbon, check the water content and cover the pile with a tarp.

Does it smell bad? Good compost piles don’t smell bad. If it smells foul, add more carbon.

Adding compost to design

If you live in frosty climates like I do, composting like this is limited to the warm seasons. However, if you have a greenhouse and are willing to sacrifice some space for a pile, you can compost inside the greenhouse. A nice little feedback effect occurs where the heat of the greenhouse allows the thermophilic bacteria to take hold, which, in turn, help to heat the greenhouse. There are people who heat their greenhouses with compost every winter. Similarly, larger piles that are not turned can heat water by running plastic plumbing pipe inside the tube. French innovator Jean Pain used to heat water to 60ºC in 40-tonne piles that would cook for 18 months.

Happy composting

Leave a Reply