Sensationalist title, yes, but unfortunately swales can cause damage, or even loss of life. When designing and building earthworks, “Don’t kill people” should be your first rule. I’m going to highlight 3 situations in which these water-harvesting earthworks could be dangerous and perhaps even fatal.

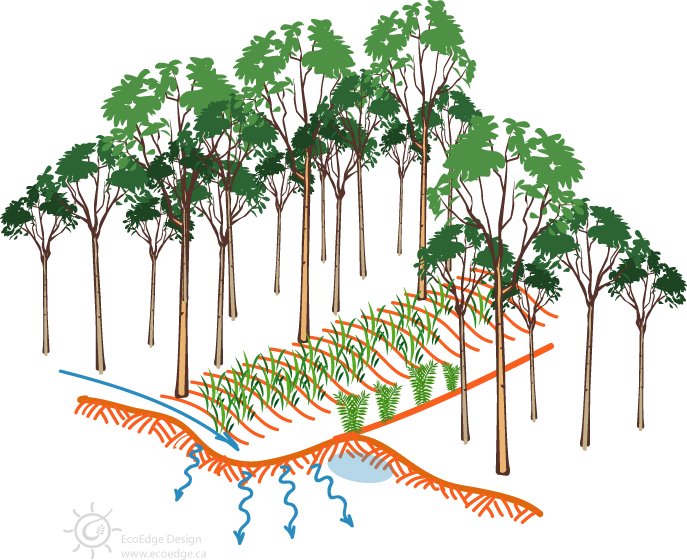

The swale is a water-harvesting ditch on contour.

You’ve Heard of Quicksand. How About Quick Clay?

When I get a call from a client who is east of me inquiring about earthworks, I immediately head for a soil map. The reason is that much of Eastern Ontario was covered by the Sea of Champlain around 10,000 years ago. Here silt, clay and organic matter were deposited in the sea’s saline environment, leaving a deposit of a particular kind of clay known as Leda clay, quickclay, or Sea of Champlain clay. The salt in the water acted as a cohesive agent. When the sea disappeared, this clay was then exposed to fresh water from rainfall, washing away much of the bonding properties of the salt, leaving the very unstable structure of the Leda clay.

Under pressure, or sometimes when highly saturated with water, Leda clay can liquefy – something which has triggered a number of landslides in Eastern Ontario. If you place a swale somewhere, you are going to make the ground downhill of the swale wetter. This creates conditions that could make the ground unstable, triggering a landslide.

So what do you do in this situation? I don’t have any set rules. I look at the need for swales and if other approaches would suffice. I also look at the slope and the likelihood that the land might slide. (Keep in mind that these slides can cover a lot of area and might start a long distance off site.)

In some situations, swales just might help prevent damage. Leda clay contracts a lot when dry, which can lead to foundation damage. If sliding is not a danger, you might help a building keeping the ground hydrated with swales. Personally, I’d look to preserve moisture with mulch and ground cover in those situations, just to be safe.

In short, Leda clay makes me nervous. I’ve yet to install or recommend any swales in these situations. If you’ve had any experience dealing with quick clay, I’d love to hear about it in the comments, or via the contact form.

Video by Christian Olsen.

Trouble in Paradise

Swales can trigger landslides in tropical highlands. These hilly areas get tremendous volumes of rainfall. Forcing more water into hillside soils in these regions can trigger a slide, even when they are forested. Consider the following passage from Jared Diamond’s Collapse:

Image of tropical highland landslide by Radhakrishnansk

[O]ne European agricultural advisor was horrified to notice that a New Guinean sweet potato garden on a steep slope in a wet area had vertical drainage ditches running straight down the slope. He convinced the villagers to correct their awful mistake, and instead to put in drains running horizontally along contours, according to good European practices. Awed by him, the villages reoriented their drains, with the result that water built up behind the drains, and in the next heavy rains, a landslide carried the entire garden down the slope in the river below.

These are areas of 3 or more metres of rainfall a year. There’s no problem with available water in these regions. Don’t risks potentially deadly landslides by floating mountainsides with swales.

Swales to Stop a Leaky Basement? No

As mentioned above, swales make the area downhill of the swale wetter. I had someone near the waterfront in Toronto contact me a few years back about doing some work on her property. Her house was at the bottom of a bluff, and she was wondering about swales above her home to keep the water out of her basement in the spring. In this situation, there was the increased risk of sliding, as well as a good guarantee that spring flooding would be made much worse. Sometimes the best advice is not to do anything. I was happy not to ruin her home with swales and I suggested some drainage to carry water away from the uphill side of the home.

Leave a Reply