“What do you do with bulrushes, or do you do anything?” Jim asked. “It seems like they get into every pond I dig.”

Jim was the excavator operator on a dam I was installing on Circle Organic Farm in Millbrook, Ontario. I told him that as long as it attracts wildlife to the site, it’s welcome. I told Jim that it will really help the farm to have wildlife come in and cycle nutrients through the site. “Anything is welcome, as long as it craps before it leaves.” This led to a discussion about the loss of our regions phosphorus transport system with the loss of the passenger pigeon.

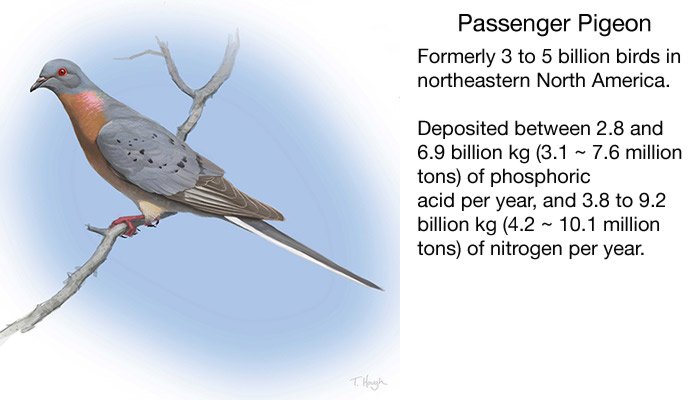

The Northeast’s phosphorus supplier

Once upon a time, there were between 3 and 5 billion passenger pigeons. Each pigeon produced around 11.5 kg (about 25.4 lbs) of guano per year. Add that up and you get a lot of poo. The passenger pigeon would deposit between 2.8 and 6.9 billion kg (6.2 to 15.2 billion lbs) of phosphoric acid each year, and between 3.8 and 9.2 billion kg (8.4 to 20.3 billion lbs) of nitrogen each year.

To give you an idea of how important this was to the ecosystem, over the whole of the U.S., farmers apply 7.9 billion kg of nitrogen to farmland each year. The passenger pigeon did it just in the northeastern region of North America.

Passenger pigeons were far from the only player in the fertility game. Click through the animals on the infographic below to see their phosphorus contributions. Whales, for instance, once cycled 340 million kg (750 million lbs) of phosphorus from the ocean depths to the surface. Whales often dive deep to get their food, then defecate near the surface. The effect is to cycle nutrients from the deep ocean to the surface, making them more available for life there. Nutrients near the surface, in turn, can then spread to terrestrial systems. As these systems have gone into decline, nutrient availability has suffered. This matters because this is a problem we all have to solve (in so far as we are interested in surviving, at least). [See http://www.pnas.org/content/113/4/868.abstract]

Click the animals to see their former and current phosphorus contribution:

For the permaculturist

If you are a permaculturist or other designer of sustainable systems, this means you will have to have respect for zone 5. [For a review of the permaculture zone, jump over to the Design Fundamentals I course. It’s free.] Zone 5, for those who don’t know, is the portion of a site that is left wild. It is used as a place to forage some foods, as a reservoir for wildlife, and as a model of a natural system to study and learn from.

As a reservoir for wildlife, one of the roles it carries out is to enhance the cycling of nutrients on the site. A lot of people would view zone 5 as wasted space that could be generating an income. However, any shortfall between the amount of nutrients cycled by wildlife or captured by plants on the site will have to be imported. In other words, you will have to pay to import any shortfall in fertility on the site.

It is also worth mentioning the significant role that preserved wild areas contribute to pest control. If you have a site that is just a field of all crop, you have a pest smörgåsbord. Wild areas serve as reservoirs for all species, pest and predator alike, which help to reduce crop pests. [See Gurr, Wratten, et al. (2004) Ecological Engineering for Pest Management: Advances in Habitat Manipulation for Arthropods, pp. 165-180. CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, AUS.]

The takeaway

The message here is that as nature goes about it’s business, it is helping to keep you and your business alive. Make space for it. Make a lot of space for it. Zone 5 areas are a part of the productive, energy-catchment systems that you need to make your site sustainable.

Stick around, I’ll answer these questions, increase your designer’s toolbox, and even tell you how to make one of these guys (

Stick around, I’ll answer these questions, increase your designer’s toolbox, and even tell you how to make one of these guys (

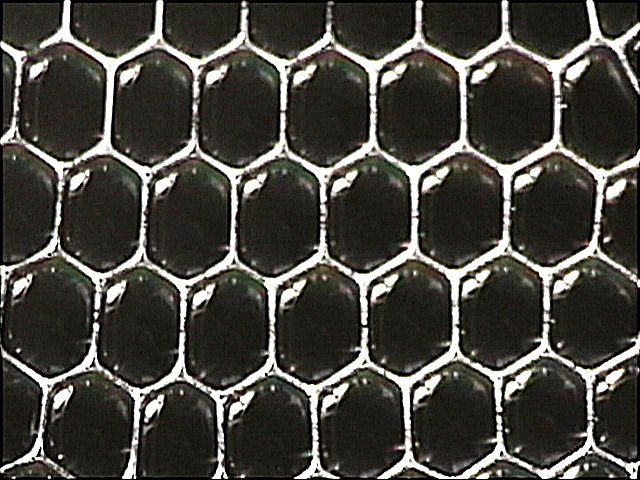

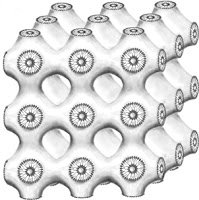

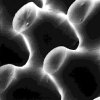

We see this form when we take a look at the skeleton of a sea urchin. This form is stronger than reenforced concrete, giving it promise as a design feature for structures where lightweight strength would be needed.

We see this form when we take a look at the skeleton of a sea urchin. This form is stronger than reenforced concrete, giving it promise as a design feature for structures where lightweight strength would be needed.

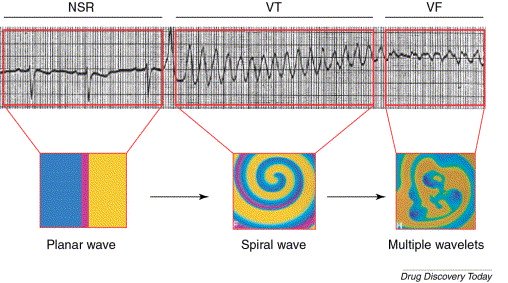

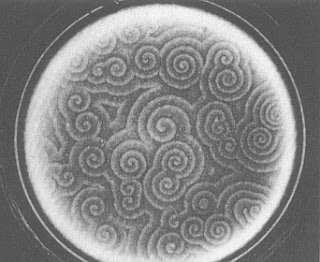

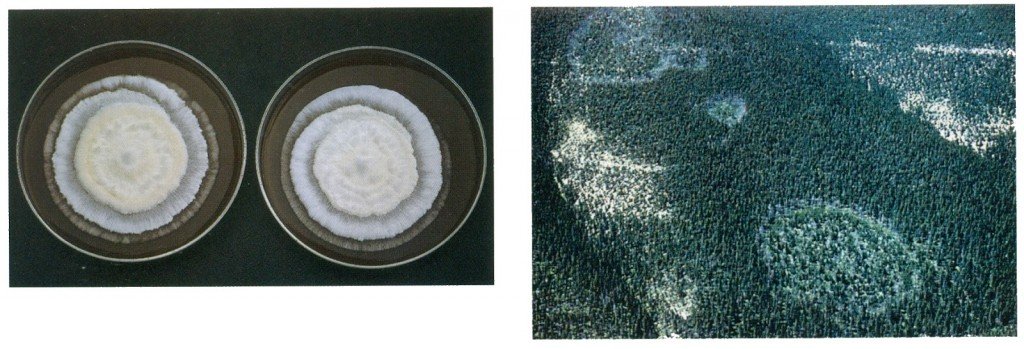

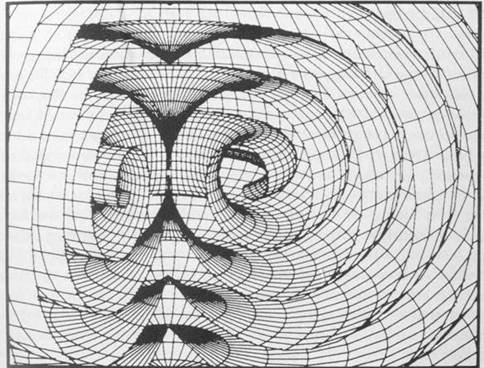

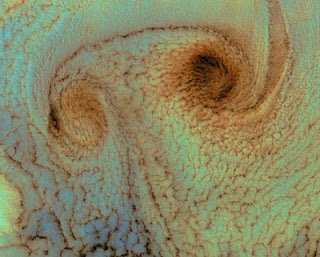

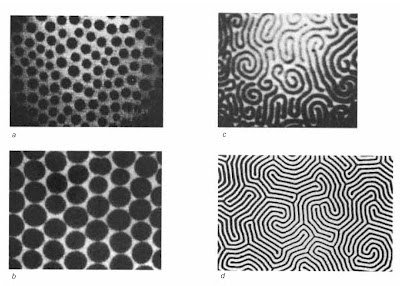

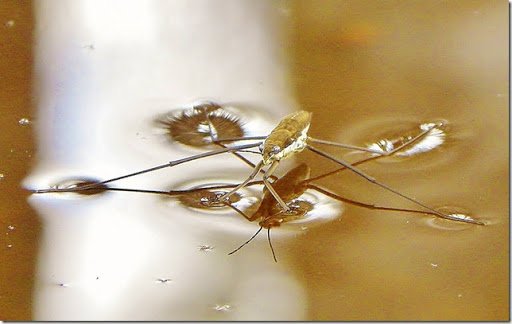

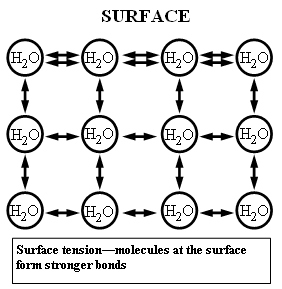

When we look at the natural world, everywhere there are patterns. The universe has mathematical templates by which form arises, and patterns reveal a beautiful order to the world.

When we look at the natural world, everywhere there are patterns. The universe has mathematical templates by which form arises, and patterns reveal a beautiful order to the world. It is a common error to think that there is a tremendous amount of symmetry in a snowflake as

It is a common error to think that there is a tremendous amount of symmetry in a snowflake as